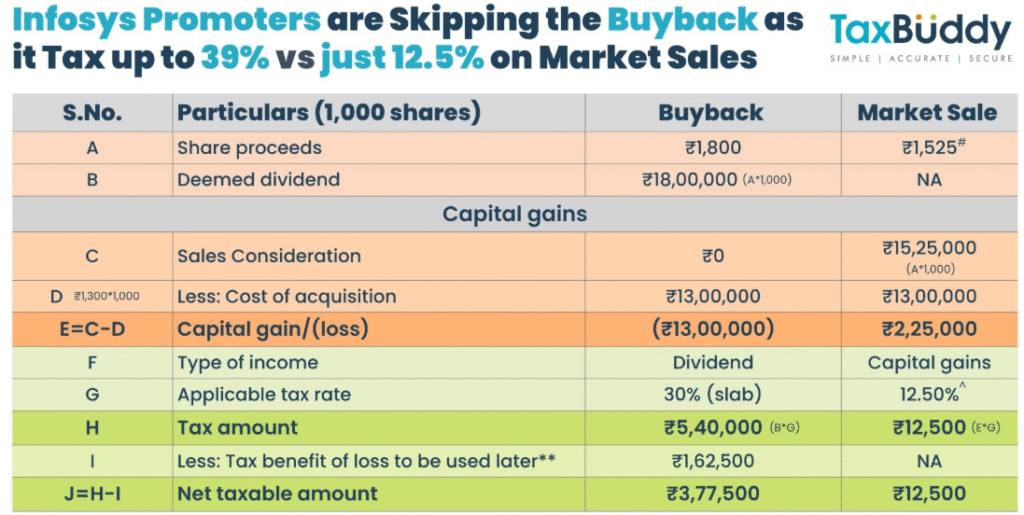

Infosys’ record ₹18,000 crore share buyback has been overshadowed by a significant non-event: the decision by its promoters and high-net-worth investors to skip the offer. This non-participation is a direct result of India’s new tax law, which has rendered corporate buybacks financially unattractive for top-bracket shareholders.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Here is a breakdown of the “inefficient buyback tax regime” that has fundamentally altered the math, turning a premium offer into a net loss for high-income investors:

1. The Core Tax Shift: Dividend Income vs. Capital Gains

Effective October 1, 2024, the tax burden for buybacks shifted entirely from the company to the individual shareholder, classifying the proceeds as ordinary income.

| Scenario | Old System (Pre-Oct 2024) | New System (Post-Oct 2024) |

| Tax on Investor | Capital Gains Tax (only on the profit/gain) | Income Tax (on the entire receipt) |

| Tax Rate for Promoters | Lower capital gains rate (Long-Term Capital Gain) | Highest personal income tax slab ($\approx$ 35.88% with cess) |

The Financial Killer: Under the new rule, the entire payout of ₹1,800 per share (in the Infosys case) is taxed at the highest slab rate. As experts note, a 35.88% tax on ₹1,800 is $\approx$ ₹646 per share. This leaves the promoter with a net amount of only ₹1,154, which is significantly less than the market price (around ₹1,472), making the buyback economically unviable.

2. The Double Blow: Upfront Tax and Deferred Loss

The new tax framework creates a damaging distortion by denying an immediate offset for the original cost of acquisition:

- Upfront Tax: The investor pays full slab-rate income tax on the gross buyback receipt.

- Artificial Capital Loss: Since the entire receipt is taxed as “dividend income,” the original cost of the shares is not allowed as a deduction. Instead, this cost is “converted” into a Long-Term Capital Loss (LTCL).

- Limited Relief: This LTCL can only be set off against future Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG) over the next eight years. It cannot be used to offset the dividend income taxed in the current year.

In Short: High-net-worth investors face a double hit—they pay a high, immediate income tax while the resulting capital loss can only provide deferred, conditional relief.

3. Conclusion: The Appeal is Gone

The new regime, intended to end the tax arbitrage between dividends and buybacks, has now “penalized” high-income shareholders.

As TaxBuddy noted, the earlier system ensured symmetry—the company paid the tax, and the investor received the capital gain benefit. The current complexity and high marginal tax rate have made buybacks far less efficient than simply selling the shares in the open market, causing a visible decline in corporate buyback activity and prompting promoters like those at Infosys to stay away.

Comments are closed.